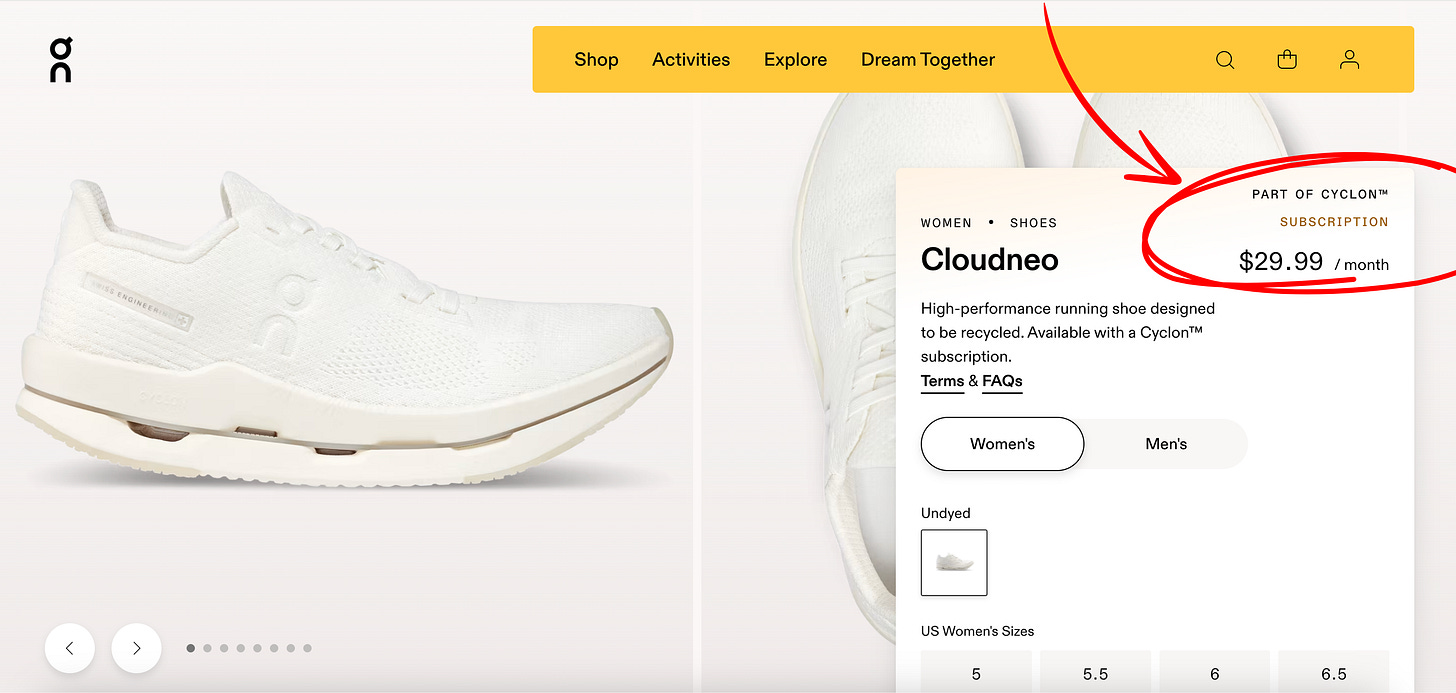

ON wants you to subscribe to your running shoes.

That’s right: pay $29.99 a month for this pair of Cyclon running shoes and at or after 6 months you get the opportunity to trade them in for a brand new pair. Rinse and repeat as long as you keep that subscription active.

You may have heard of a little something called subscription fatigue. And after the “let’s send Millennials a bunch of crap in a box era” (a la, Stitch Fix, FitFabFun, Birchbox, Barkbox, etc.) and The Great Streaming Service Proliferation of 2019-2022 (Disney+, AppleTV+, Discovery+, Paramount+, Quibi, Peacock, etc.) we basically all have it. It’s that “GET ME OUT OF HERE” queasy feeling in your gut you just got when I told you about the concept of a “shoe subscription”. A shoescription, if you will.

I had that feeling, too, when I first saw “$29.99 per month” on a pair of SHOES! I wanted to throw up. But because I am who I am, I also wanted to read everything I could about this program to try and figure out why they’re doing this.

Spoiler alert: I know I love to be a contrarian but, I actually think this could be a really smart move that allows ON to do something I haven’t seen any other company do: design their business model for sustainability, such that the profit motive and sustainability objectives are actually aligned.

Woah, back up: how is this related to sustainability?

The stated intent behind the Cyclon Subscription is that the Cyclon shoes that are exclusive to the subscription are recyclable. In other words, you can only buy these recyclable shoes if you’re subscribed.

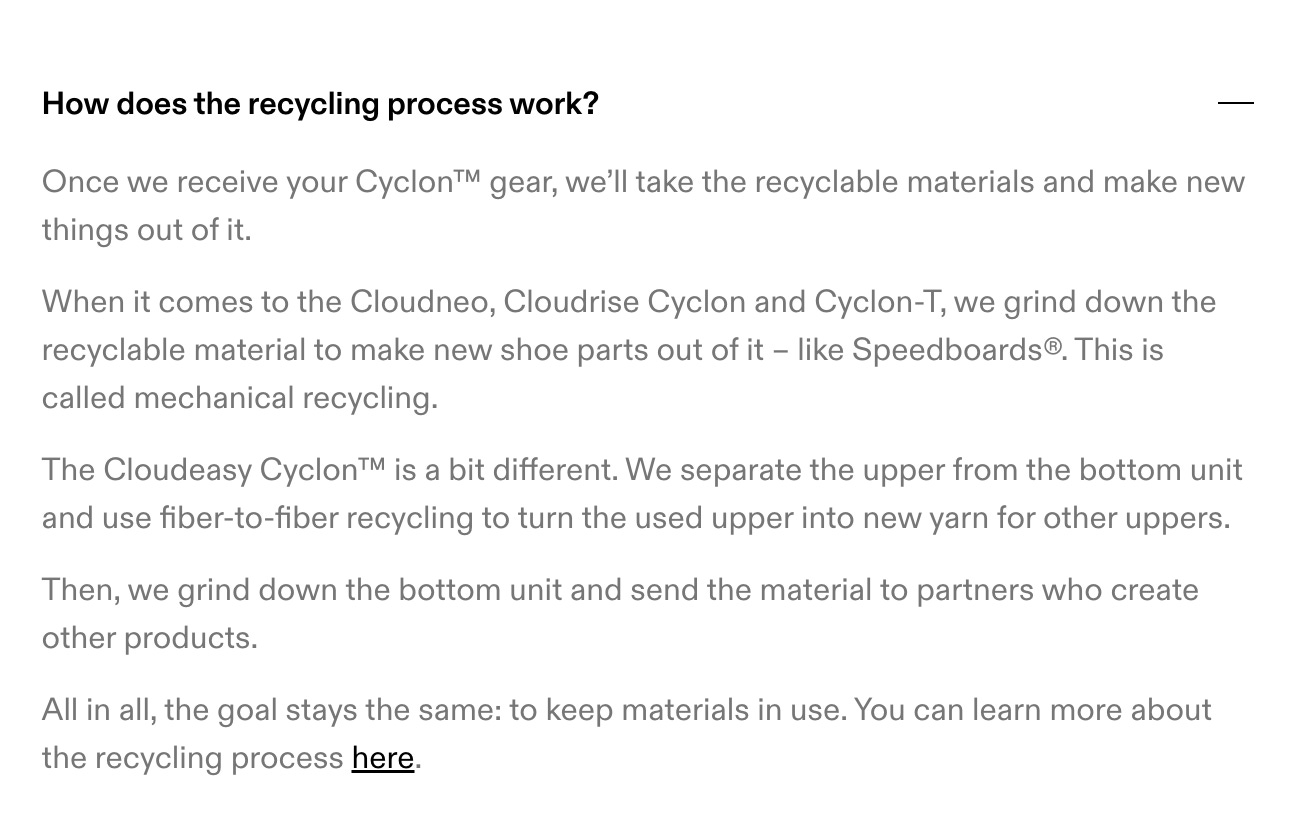

It seems these particular shoes have been designed by ON to be disassembled after you send them back in. And then certain parts of the shoe are mechanically recycled into other parts of other new ON shoes.

Yeah duh, isn’t that how recycling works?

We have to talk about how this IS very different from many “recycling” programs you see touted by brands like H&M or Zara.

The truth is that it is incredibly difficult to collect post-consumer mixed textiles, pick them apart, and turn them into new textiles. That’s because for this recycled textile to be commercially viable, it needs to be consistent. For someone to take that fabric and make something new out of it, you need to be able to say, “this output is 100% recycled polyester. It comes in this color, and it has these consistent properties”.

But to have any consistent output, you need a consistent input. And collecting any old clothes that your customers drop in a bin isn’t a consistent input. It’s wildly inconsistent.

This means that many - I would frankly say most - cases where you hear that clothes or shoes are being “recycled” by clothing brands, what’s really happening is that the brand is partnered with a third party provider who has a warehouse where these items are shipped. There they are sorted, typically into three categories:

Things that are re-sellable, as-is in their current form. A lot of times, these get re-sold into the rag trade and end up in the Global South which as we know is already overwhelmed with our clothing.

Things that are aren’t re-sellable, but are good enough to be down-cycled into fibers for another use where the intake stream doesn’t need to be totally consistent. That use is almost always something really boring like insulation

Things that are not usable at all, and just get sent straight to landfill

So, while some of these uses may be marginally better than landfill, they are a are far cry from what they hope you imagine when they say “recycled”. When you put your clothes in these bins or bags, they aren’t magically transforming into new t-shirts.

[As an aside, the Changing Markets Foundation did an excellent investigation into these programs where they attached bluetooth trackers to 21 items in perfectly re-sellable condition to see where they *really* ended up. TLDR: only 5 of those 21 items ended up being re-sold, and all the others were either downcycled (3), destroyed (4), shipped to Africa (4) or just…stuck in limbo (5).]

The point is: a recycling program like ON’s where the components are sorted into clean input streams that actually become a material that is used in the same type of product is rare.

And, it’s really hard to do.

When capitalism and sustainability aren’t friends (hint: it’s almost always)

Why haven’t we overcome this by now? Like all these issues are solvable, right? Given how much companies tout recycling and how much we consumers care about sustainability, there should already be more true recyling programs like this.

But what we don’t talk about enough is that the financial incentives of capitalism are very, very often in direct conflict with making real progress on sustainability. That conflict is why we don’t make more progress (IMO).

In the context of retail and apparel, the problem pretty much boils down to this: when a company like ON sells a pair of shoes or piece of clothing straight-up, that’s it for them. That was THE big moment. The register lit up and the money hit the bank - and after that point, they no longer have any real financial incentive to care at all about what happens to the item next.

If anything, dealing with the item at all after it’s sold is only gonna cost them money.

This issue is the root cause of a TON of symptoms that are annoying as hell for you personally and together add up to the fast-fashionification of our world.

Does a company really care if the item falls apart after a month in the wash? Nope! They already got their money.

Does a company really care if the item immediately goes out of trend and just sits in the back of your closet? Nope! They already got their money.

And, does a company really care if the item quickly ends up in your “purge” pile until one day you throw up your hands and schlep it to Goodwill, in turn ending up in a landfill? Nope! They already got your money.

In fact, each of these might be a double-win for them because it means that you might just come back to them to buy something else!

Right now, the only incentive for brands to combat these post-purchase issues is public perception. But even when public perception on quality and trend seems pretty bad (see: Shein) we seem to be pretty damn forgiving of that when it comes down to it (see: Shein selling $32B+ worth of clothes every year).

So, the financial incentives just aren’t currently there for brands to really care about what happens to an item after they sell it, which means that “circularity” initiatives are half-assed or pushed to the side entirely.

Bringing it back to the shoescription

If we want to assume the best about ON’s subscription, I’d put forward the theory that they designed it this way because the subscription business model better aligns their financial incentives with their sustainability goals.

In short: it forces them to care about handling post-purchase.

Why? Because the subscription means that this is no longer a one-and-done transaction where they have no accountability for the product after it leaves their hands. ON *has* to keep taking back these shoes because the subscription model means that their customer will only keep paying them if they do.

And, once they have these used shoes filling up their warehouse, there’s a real financial benefit them to do something productive with them. I’d also bet that the set-up of this program also makes it easier to predict the volume of shoes coming back, which could make the whole program more scalable and efficient.

So if you think about it that way, it’s actually pretty innovative.

$30 times 6 months is $180 per pair of shoes. Which, is on the higher end but basically in-line with their other running shoes which run between $150 and $180.

So, if you ARE a runner replacing your shoes every 6 months, maybe it’s not crazy. Assuming of course that you do like these ones.

ONE BIG FLAW IN THE PLAN

There’s one big flaw with this idea. Recycling isn’t necessarily the end-all-be-all panacea of sustainability. In fact, I’d argue that the *most* important tenet of sustainability is to actually use our stuff as possible. But there is an adverse incentive inserted in the Cyclon Subscription model which is that any financially rational person is going to send their shoes back to be recycled every 6 months regardless of whether they’ve really been worn out or not.

Of course ON says to “run in them until you can’t run anymore”, but…if you have a pricey shoe subscription that allows you to trade in for a new pair every 6 months, let’s be honest that most people aren’t going to wait even if all those shoes have done is walk the dog a few times a week. They’re gonna max out the program.

So, what’s the net-net climate impact? Hell, I don’t know it’s not like I’m a scientist or anything.

So, do you buy it?

I know we all have subscription fatigue. But if embracing alternative business models like ON’s shoescription is what it takes to tip the scale towards real sustainability for businesses and our society at large…are you willing to do it?

I love your business analyses, and really hope you continue doing them! I found you via tiktok and I love the way you breakdown P&L's as a woman in tech, it's SO HELPFUL.

Back to the blog post, do you think there is also an aspect (that could tie back to sustainability) of them being able to predict their business a bit better which in turn would lead to them making less excess shoes?

Thank you again for these breakdowns, love them!

Super interesting! (yes I know I'm commenting on a really old piece, but I wanted to check more of your work after seeing your great Quince analysis)

For me, running shoes are pretty much the only thing that a clothing subscription like this would make sense for, as I replace mine every 6-9 months to help avoid joint issues with regular running. Everything else that enters my wardrobe I expect to keep for much longer and so subscriptions just feel like overconsumptive bs. But interesting to know this could actually be a beneficial model